Art has a way of calling to certain individuals, often from an early age, shaping the way they see and interact with the world. For John Todd Paxton, that calling first took hold in high school, where he immersed himself in every art elective available. Though his formal education led him into graphic design and illustration, the creative journey was anything but linear. It wasn’t until 2007—after an unexpected opportunity to purchase a

foundry—that sculpture and metalwork became central to his practice.

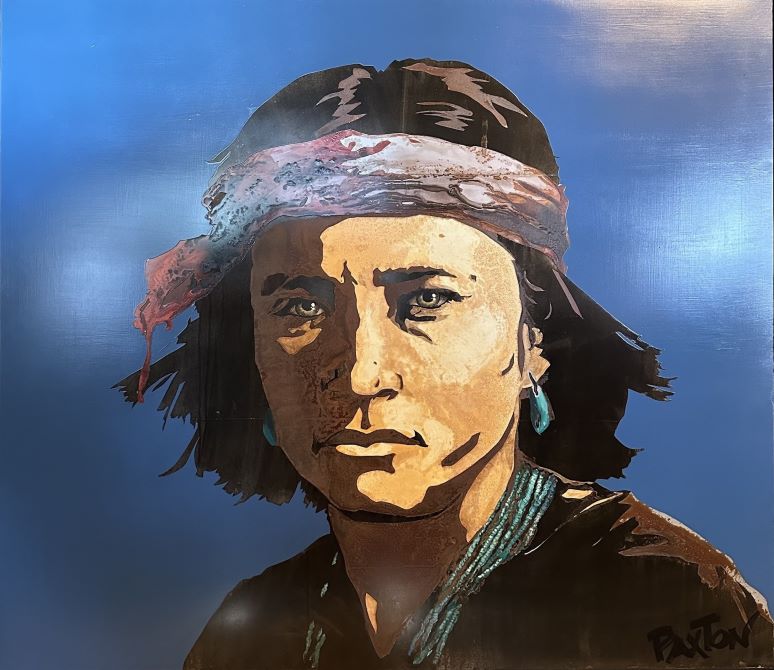

From that moment on, Todd’s artistic path was defined by experimentation, discovery and an unrelenting drive to forge something new. Working with large-scale sculptures and innovative steel paintings, Todd has developed a unique process that blends natural patinas with intentional control, allowing rust and oxidation to shape expressive, striking portraits. The interplay between raw metal and refined detail, particularly in the eyes of his subjects, creates an emotional depth that invites viewers to engage on a personal level.

Beyond the technical aspects of his craft, Todd finds the greatest reward in the emotional responses his work elicits. Through constant experimentation, refining techniques and drawing inspiration from fellow artists, he continues to evolve.

In this interview, Todd shares how he developed his unique patina-on-metal paintings, why he likes to work in large scale and what he finds most rewarding about his work.

Q&A with Todd:

When did you know art was your calling?

From an early age. In high school, you can take art electives and I took every art elective so many times that the teacher said, ‘Just do whatever.’ In college, I went to school for graphic design and illustration. I did that for a short while but then did all kinds of other things in between. But I always loved and did art, but not sculpture. That happened in 2007 when I bought a foundry.

I had a friend who was working at a foundry and they were going to

close it down. I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can buy it. We can get it going and I can start getting into the art field.’ And that’s when I started sculpting. The painting––this style of painting on steel––I actually developed at the Celebration of Fine Art. It was the first place I debuted it and it went well. Now, I’m six years into doing paintings like this. Each year is a new discovery of different ways to do this. It’s an atypical art form.

Have you always worked in large format?

I didn’t start big, but I have found over the years that that’s so attractive to me because part of the statement you make is affected by size. When I make a big giant face, it’s hard not to have a conversation with it from long distance away. When I make a big painting, its presence adds to the statement that I’m making. My paintings just start to lose their energy in the smaller size and I don’t love it as much. And with sculptures, I love it when it’s 10 foot tall and you look up at it and just have this feeling of “Whoa!”

How did you develop your patina on steel pieces?

I got into a studio where I was going to have more wall space. I was just showing sculpture and I realized I need something good on the walls, but I knew I didn’t want to do what everybody’s doing. I’m always trying to forge a new path. I wanted to do steel with patina like I do on the bronze sculptures. Initially, I thought I would do abstract––I would just let the patinas do what they were going to do and it would look cool. But over that summer of trying to figure out what I was going to do, I came up with this technique of trying to control where the patina goes, and with that, I was able to make a portrait. I’m able to control it just enough to allow the patina to do its special things, allowing the chemical reactions to happen while at the same time controlling it so that it becomes a recognizable figure that you connect with.

It has developed over time with different techniques and different patinas. Then I started focusing on the eyes because I wanted to make sure people could get involved and recognize it as a person. We connect through the eyes. That’s why I go more realistic with the eyes than the rest of the painting.

What do you love most about the creative process?

I love the creative process because you become like a mad scientist––like you’re going to make something new. You start figuring out through different things that you put together to make that whole, and all that you are comes out. Your voice comes out. And when it starts to take shape, there are certain parts in the process where you go, ‘Ooh, I’ve got something good,’ and you know that it’s going to work well.

Then when you have come to a certain level of completion and somebody comes through and says, ‘Oh wow,’ that’s also very validating. It allows you to keep going further, all the way to the finish––to the end of the creation––and now it’s living. It’s there. And watching people connect with, and have some sort of emotion with, what you have created, that’s extremely rewarding.

How do you keep yourself challenged?

Every time I see something I love that another artist has done, I’m inspired to think about what I could do next. With the paintings, it’s developing new processes. It’s how I can refine the pieces so they connect easier with the audience. My pieces are big and they’re bold, and that’s not always what people want. So, I’m trying to figure out how to balance the things that I love with what people will identify with and really love, too. For the sculpture, it’s always learning anatomy, portraiture, history and what stories I can tell from all of those things put together. It allows me to have a vehicle to tell a story that is attractive.

What is the most rewarding aspect of what you do?

Every time someone goes, ‘Wow,’ that makes me feel good. That’s very rewarding because you’ve done something that makes them have a visceral reaction to it.

But there was one time in a gallery in Santa Fe where I have an eight-and-a-half-foot tall monumental sculpture. He’s a big, very imposing, mean-looking warrior guy. His story was all about the fight that we have and how if we prepare and we get steadfast, we will be victorious, but there will be sacrifices to have that victory.

I was walking through [the gallery] and these two little Spanish ladies were standing up and staring up at this sculpture and they had tears coming down. I asked if they were ok, and one of the ladies said, ‘This means so much to me.’ That is the best reaction. She had a very emotional reaction to the piece, which I wouldn’t think she would identify with, but she did. She was that eight-and-a-half-foot tall warrior at that moment, and she had had a fight. She had gone through it and had been victorious, and now she was having this deep emotional connection with that piece of art that I had made.

What keeps you coming back to the Celebration of Fine Art?

The Celebration is amazing. There’s connection. You are in front of people that you never would be able to be in front of. It’s like art camp. I’m around so many other amazing artists, it’s inspiring. I get to have awesome conversations about creativity and creating. Those types of conversations happen a lot here. And the collectors that roll through and ask questions about why I’ve created. It’s so fun to talk about art with people in a gallery and I do spend some days in the galleries sculpting and talking with people, but it’s so very few. Here, it’s every day, all day. And that’s very rewarding to see the effect your art has on the people who see it immediately.